Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Double Agent

We're going to take a moment to raise our twenty-four-ounce mug of coffee to Nelly Dean. Thanks, Nelly. Without you, there would be no Wuthering Heights. Nelly is our eyes and ears on the ground.

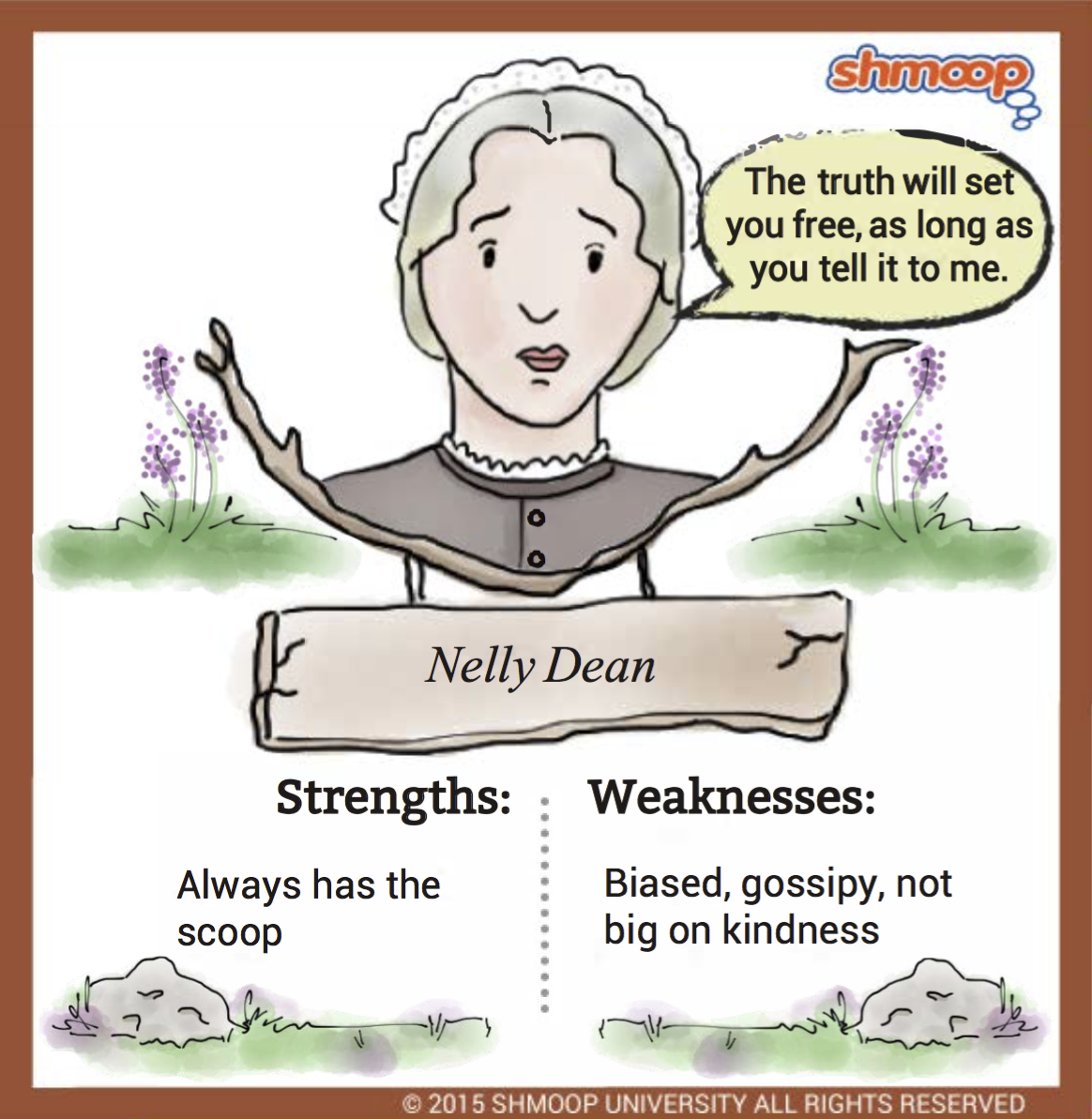

As Lockwood figures out pretty quickly, Nelly Dean has the inside scoop on the Earnshaw-Linton melodrama. She is trusted by the members of both houses, so she is a pretty good source for the story. But that doesn't necessarily mean that we like her.

At the same time, Nelly has been excommunicated from Wuthering Heights at least two times that we know of. When Heathcliff first arrives as a child, she leaves him on the landing of the stairs and, as she tells Lockwood, "Inquiries were made as to how it got there; I was obliged to confess, and in recompense for my cowardice and inhumanity was sent out of the house" (4.50). She further confesses, "Hindley hated him, and to say the truth I did the same" (4.52).

All of this suggests that the very person we rely upon for the facts was a participant in Heathcliff's childhood humiliations. Though not nearly the brat Hindley was, Heathcliff never earned Nelly's affections, and though they have a few moments of tenderness, Heathcliff basically takes her for the instigator that she is. He later forbids her to remain with young Cathy when she moves to Wuthering Heights, which really angers Nelly. When Heathcliff reaches the climax of his manic behavior, Nelly wonders, "Is he a ghoul, or a vampire?" (24.46)—only to remind herself of the infant he once was and that such musings are absurd.

Another issue to consider is Nelly's reliance upon several other narrators to piece together the story—Isabella, Dr. Kenneth, gossipy villagers, and credulous shepherd boys. While she is a much more useful and informed narrator than Lockwood, she is also flawed, biased, and overly identified with the Lintons... so you have to be careful about her. When Nelly begins narrating to Lockwood, we don't suddenly get the "real story," but rather another representation of the "truth."

It's easy to forget that the novel is Lockwood's journal, which is itself a recording of Nelly's oral narration. Lockwood hopes to find in Nelly a "regular gossip," though she believes herself to be a "steady" and "reasonable" character whose familiarity with books qualifies her as a storyteller. She will indeed provide some clarity to the complicated family tree, but she is no omniscient narrator—not by a long shot. By her own confession, she and the other villagers (several of whom fill in the gaps of her story) don't like outsiders, and they have a tendency toward superstition.

What's more, Nelly seems to find the whole conflict between the families pretty entertaining. But, to be fair, so do we.