Character Analysis

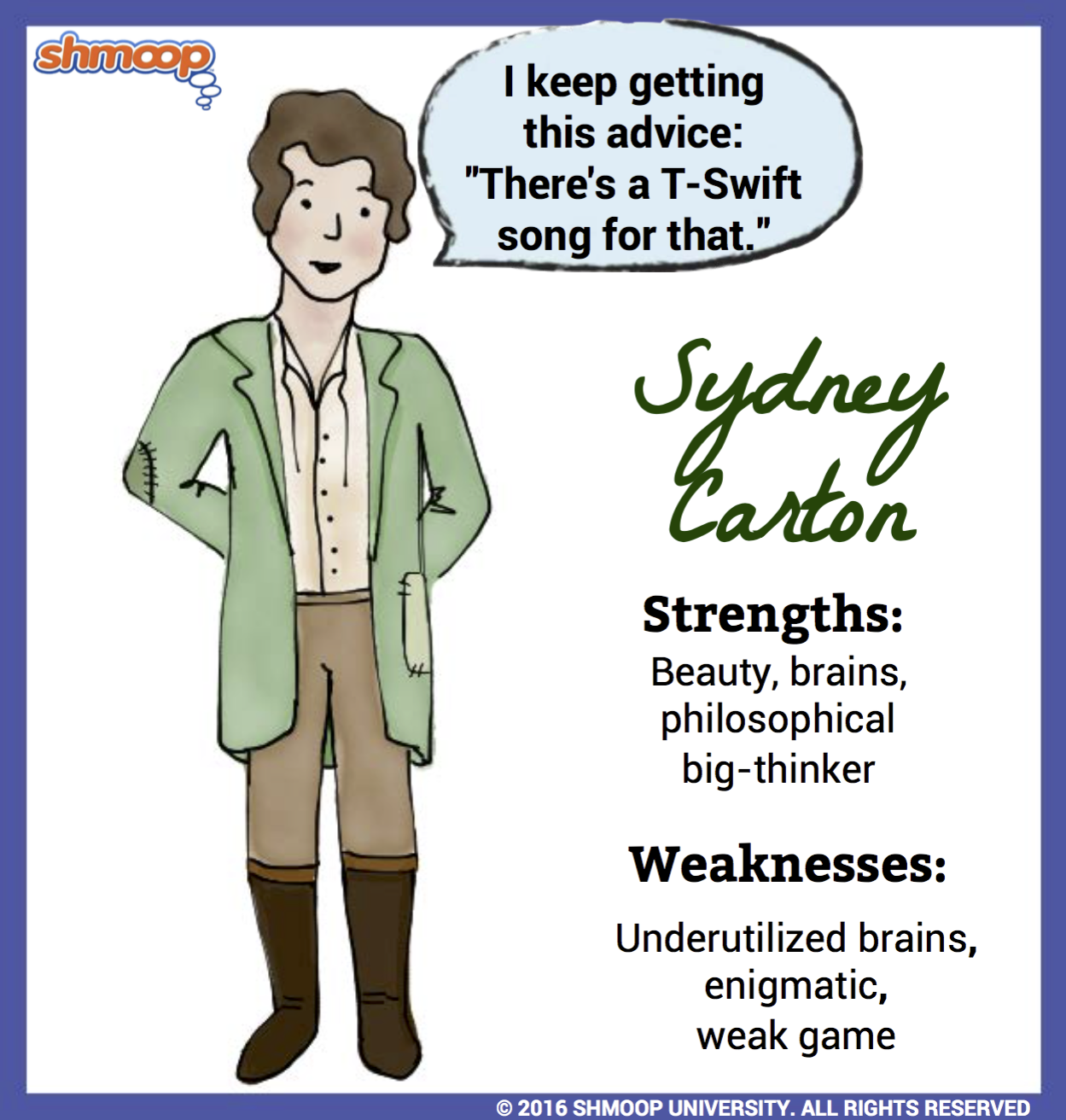

(Click the character infographic to download.)

Sydney Carton’s a tough nut to crack. At twenty-five, he’s obviously brilliant: he manages to make one of the stupidest men in London, Mr. Stryver, into one of the most prominent lawyers of his time. He’s also rather good-looking… at least, we’re pretty sure he is. See, he looks exactly like Charles Darnay. And Darnay is definitely attractive. Which means Sydney can’t be all that hard on the eyes, right?

So, with looks and brains, Sydney should have the world at his feet… right? Well, not exactly. Orphaned at a young age, Sydney spent most of his youth writing homework for his classmates. He spends his adult years being the brains behind Stryver’s brawn. (Okay, Stryver’s not exactly brawny, but you get the picture.) Strangely enough, Sydney doesn’t exactly seem like the sort of scrawny kid who got his lunch money stolen every day.

So why does he settle for living other people’s lives? Ah, that’s a good question. In fact, it’s the question that’s troubled readers of A Tale of Two Cities for, well, centuries. Believe it or not, no one has come up with any good answers.

Sydney and the Existential Crises

Perhaps part of the reason that Sydney remains so impenetrable is that Dickens just doesn’t give us much to work with. Sydney’s unhappy because Sydney is convinced that he should be unhappy. It’s as simple as that.

The problem, of course, is that Sydney seems far too intelligent to wallow in his own masochism. That doesn’t seem to bother Dickens, however. Sydney may be given to reflection and introspection (after all, he does spend most of his nights wandering the streets of London), but he rarely says anything that would allow us to understand why he’s given himself over to the Dark Side.

We don’t mean to say here that Sydney’s evil. He’s just trying to eat himself up inside. When he does explain his melancholy, it’s in cryptic phrases like these:

- "I am like one who died young. All my life might have been" (2.13.17).

- "I am a disappointed drudge, sir. I care for no man on earth, and no man on earth cares for me" (2.4.70).

- "I am not old, but my young way was never the way to age. Enough of me" (3.9.57).

Like our narrator, Sydney tends to be a big-picture thinker. What’s the purpose of life in general? More specifically, given the current crummy state of affairs, how can his life hold any meaning at all? In the rare moments when he does explain his own actions, it’s through philosophical reflections like these. Needless to say, they aren’t the sort of thoughts that win friends or charm the ladies.

That brings us to our next point:

Sydney and Love

Sydney may not be the life of the party, but he can be strangely devoted to the things that he does care about. Take Stryver, for instance. The guy’s an all-out jerk, but for some reason, Sydney sticks with him.

Sydney’s love for Lucie is just a little bit easier to understand. After all, everyone loves Lucie. (Didn’t they make a show about that in the 1950s?) Sydney watches her when no one else is looking. After all, he’s the first to notice that she faints during Charles’s trial. The social cache that he gains from saving Charles allows him to visit the Manettes on a regular basis, but he never seems to get beyond an awkward middle-school-type crush on Lucie.

Remember when you liked that girl in sixth grade? You liked her so much that you decided you couldn’t be nice to her… so you said mean things about her to your friends. Maybe you were even rude to her whenever you met. Sure, it’s not very effective… but it’s understandable.

That’s how Sydney is around Lucie. Despite his awkward (or even hostile) attitude, however, Lucie has come to play a very important role in Sydney’s imaginative life. Given that Sydney lives in his head most of the time anyway, maybe it’s actually not so horrible that he doesn’t get to marry her. The idea of Lucie allows Sydney to throw all his devotion at the feet of a goddess. Perhaps that’s all he really wanted in the first place.

Sydney and Charles

He may be content with never having Lucie, but that doesn’t mean that Sydney has to like Charles. For one thing, they’re just too alike. Sydney and Charles look alike. They’re both smart, and they’re both essentially good. Charles, however, seems to have gotten all the good things in the world. Sydney got the short end of the stick. Charles marries Lucie and lives a happy life in Soho. Sydney paces the streets outside Lucie’s house every night.

The comparison between the two characters is almost farcical. How can two people with such similar traits face such different fates? Moreover, why in the world would Sydney give his life to save Charles? Couldn’t he just care for Lucie after Charles’s death? Sydney’s apparent dislike of Charles makes his sacrifice all the more unimaginable.

Sydney and Christ

Muttering "I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live: and whosoever liveth and believeth in me, shall never die" (3.9.89), Sydney paces through the streets of Paris on the night before his death. His litany could be a way for Dickens to show readers that Sydney is a man of faith, but it has also prompted generations of critics to read Sydney as a Christ-like figure.

After all, the parallels aren’t that hard to find. Sydney’s Biblical reference alludes to Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead. Hmm… rising from the dead. Does this sound familiar? Moreover, like Christ, Sydney sacrifices his life for the good of other men.

Okay, we won’t beat you over the head with the similarities. You get the general idea. The magnificent thing about this parallel, however, is that it’s so unexpected. Sydney doesn’t seem to have what it takes to be a hero at all. Then again, Sydney tends to see things in apocalyptic terms. He might not be able to act in his own self-interest, but, paradoxically, he’s completely willing to sacrifice everything so that another man may live.

Sydney’s last lines become a gorgeous, forgiving, far-reaching proclamation of hope for the future of humankind:

I see a beautiful city and a brilliant people rising from this abyss, and, in their struggles to be truly free, in their triumphs and defeats, through long years to come, I see the evil of this time and of the previous time of which this is the natural birth, gradually making expiation for itself and wearing out. (3.15.46)

The peaceful, prophetic tone of Sydney Carton’s last words makes him one of Dickens’s most memorable (and most inscrutable) characters. We almost wonder if Dickens made him inscrutable on purpose. If he’s impossible to understand throughout the novel, then his sacrifice will seem all the more sublime at the end.