Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

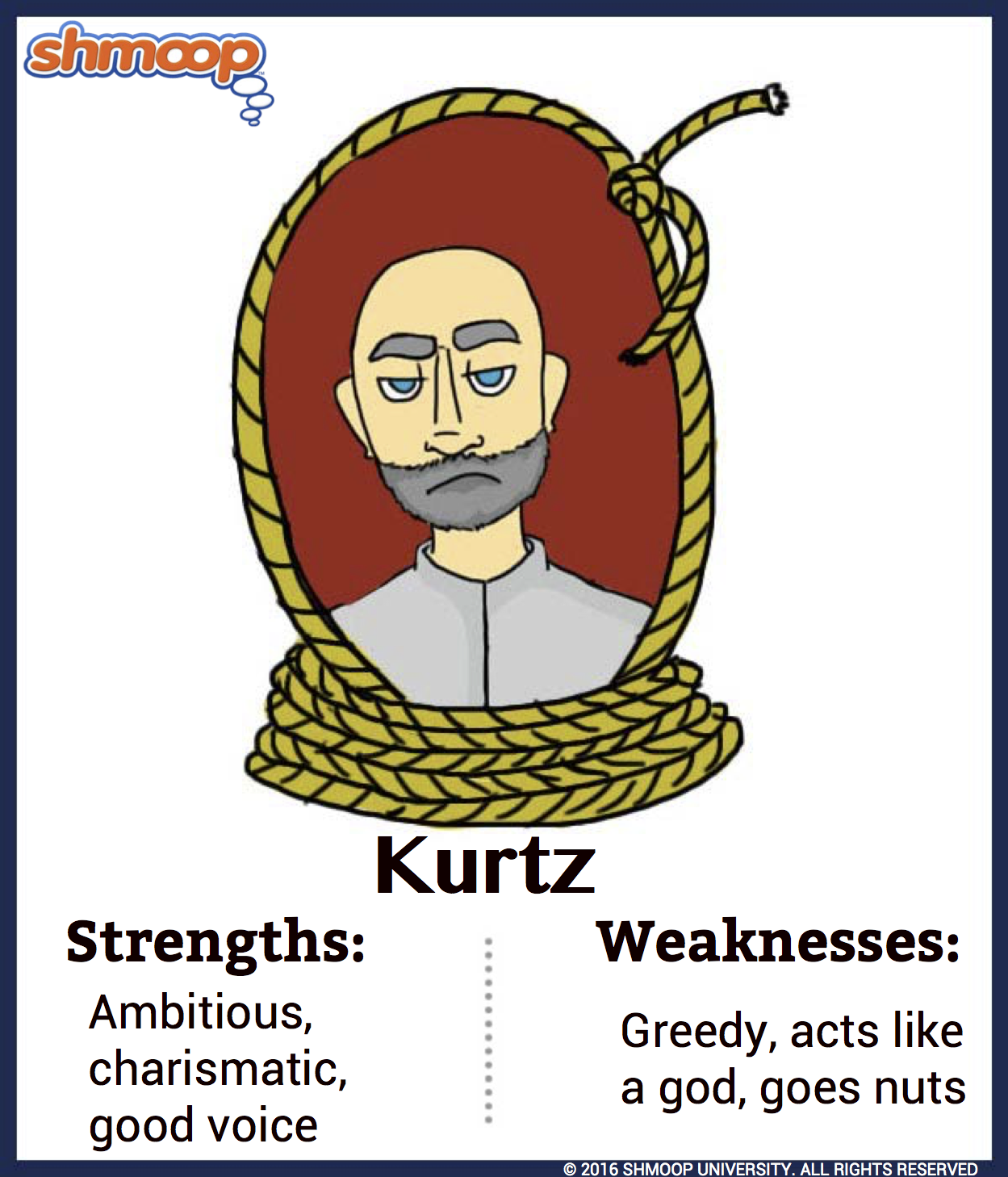

Mr. Kurtz is a star agent of the Company who works in true ivory country, deep in the interior of Africa. Also, he goes crazy and dies.

Will the Real Mr. Kurtz Please Stand Up

Everyone who knows Kurtz (even his fiancée, who doesn't know him at all) agrees that he has all the ambition, charisma, and eloquence to achieve greatness. As the Intended says—although she's not the most reliable witness—he's a man of "promise," "greatness," a "generous mind," and a "noble heart" (3.66).

Come to think of it, everything we know about Kurtz is secondhand. So, let's start with what we do know.

It's a Jungle Out There

Kurtz represents a normal—if ambitious—man who realizes that to thrive in the Interior, he has to act like a god, someone who can lead these "primitive" people to the proverbial light and civilization.

But then greed gets in the way. His insatiable hunger for ivory drives him to make alliances and enemies among the native Africans, raiding village after village with the help of his African friends as he searches for ivory. His obsession takes over so much that Conrad/ Marlow even describes him in terms of the material he seeks: his head "was like a ball—an ivory ball" (2.29), and when he utters his final words, he carries an "expression of sombre pride" on his "ivory face" (3.42). The jungle has "got into his veins, consumed his flesh" (2.29), making him into a totally different man.

Maybe that's why Marlow tells us repeatedly that Kurtz has "no restraint" (2.30, 3.29). It's not as simple as "Kurtz goes to jungle; Kurtz becomes like native Africans; Heads on sticks ensue." In fact, Kurtz becomes something else altogether—something worse. (The horror! The horror!)

See, Africans do have a sense of decency and restraint. Think of the cannibals who eat rotten hippo meat instead of attacking the pilgrims whom they outnumber five to one. But not Kurtz. Kurtz has fallen a complete victim to the power of the jungle, has transformed into its "spoiled and pampered favorite."(2.29). He's basically become a child, and not a nice one, either: a greedy, selfish, and brutal playground bully.

Or as Marlow so beautifully says, the "powers of darkness have claimed him for their own" (2.29).

A Face for Radio

Marlow ends up refining his obsession with Kurtz all the way down to one particular aspect: his voice. He's not excited about seeing Kurtz or shaking his hand or talking about last night's Lakers game, he says—just hearing him talk. "The man presented himself as a voice" (2.24), Marlow says, actually breaking the order of the story's narrative to tell us that he does eventually get to talk to Kurtz. This little narrative interruption drives home just how important Kurtz's voice is.

Now consider this: Marlow, sitting on the Nellie and telling his story in the pitch-dark, is explicitly described as "no more to us than a voice" to the men that listen (2.66). And then, When he finds an "appeal" in the "fiendish row" of the Africans dancing on shore, he negates it with the claim, "I have a voice, too, and for good or evil mine is the speech that cannot be silenced" (2.8).

So is this voice business merely another tool to establish connections between Marlow and Kurtz? Maybe. If Marlow's voice is never silenced, what about Kurtz's? The guy dies, after all. But are his last words resonant for us? Does Heart of Darkness end on a note of "horror"?

Kurtz as a God

The native Africans worship Kurtz like a god, even attacking to keep Kurtz with them. But here's the irony: we're not sure whether Kurtz orders the attack or whether the native Africans do it on their own (we get conflicting stories from the harlequin). Kurtz may be a god, but he's also a prisoner to his devotees. He can order mass killings of rebels, but he can't walk away freely.

Hm. We're feeling like there might just be a little bit of symbolism here.

Ready for some more irony? Kurtz was apparently seven feet tall or so (although we figure Marlow was riding the hyperbole train here). But his name means "short" in German—which Marlow makes sure to point out, just in case we're not caught up with our Rosetta Stone cassettes. So, his name contradicts his god-like height, a discrepancy that reflects the big fat lie of his life and death, and which we're thinking means his life as a god was also false.

As for his death? You tell us.

Kurtz, Madness, and Sickness

First, is Kurtz mad? Um, yes. We think that jamming a bunch of heads on sticks might qualify, but if that weren't enough, Marlow makes sure we know that, although the man's intelligence is clear, Kurtz's "soul [is] mad" (3.29).

And then his madness becomes physical, so that his bodily sickness is a reflection of his diseased mind. His slow, painful spiral into death is marked by visions and unintelligible ravings. Parts of the narrative recount the emptiness of Kurtz's soul; this may be a commentary on the debilitating and devastating power of the wilderness to suck all the humanity out of a man.

And now for those famous final words: "The horror! The horror!" (3.43). Marlow interprets this for us, saying that these words are the moment Kurtz realizes exactly how depraved human nature is—that his inability to exert even a shred of self-control is the same darkness in every human heart. (Speak for yourself, Kurtz: there's a red velvet cupcake sitting on the counter that we're resisting quite nicely, thankyouverymuch.)

Ahem. As Marlow says, "Whether [Kurtz] knew of this deficiency [lacking restraint in gratification of his lusts] I can't say. I think the knowledge came to him at last—only at the very last" (3.5). So why do people still look up to Kurtz? We think they see in him the potential for greatness, along with charisma and ambition. And those qualities end up being Kurtz's legacy—not his madness and brutality. Is this Conrad's own condemnation of mankind's blindness?

Kurtz the Hero

Buckle up, set the airbags, and put on your oxygen masks: we have one more big idea about Kurtz: He's the result of progress.

Think about it. We know that Conrad isn't doing a simple light = good, dark = bad thing. Instead, he's suggesting that progress—moving into Africa, spreading Western culture—inevitably means taking part of the dark inside you. (Want a fancy word for this? We call it dialectics.) What Kurtz shows us is that progress isn't good. In fact, it's horrific.

In the nineteenth century, there was a general idea in Europe that history and cultures were evolving toward a better future. Western civilization was the pinnacle of human evolution, and eventually it was going to crowd out the darkness in other parts of the world.

Conrad didn't think so, but his objection wasn't the cultural relativism that makes us roll our eyes at that idea today. Today, we tend to see all cultures as valuable—different, sure, but equally worthwhile in their own way. Saying that Western culture is the pinnacle of human evolution and that we have a duty to educate people all over the world strikes many people as a little presumptuous and even silly.

It didn't strike Conrad as silly. It struck him as terrifying. Through Kurtz, Conrad shows us that the true result of "progress" is madness and horror.

Mr. Kurtz's Timeline