Character Analysis

(Click the character infographic to download.)

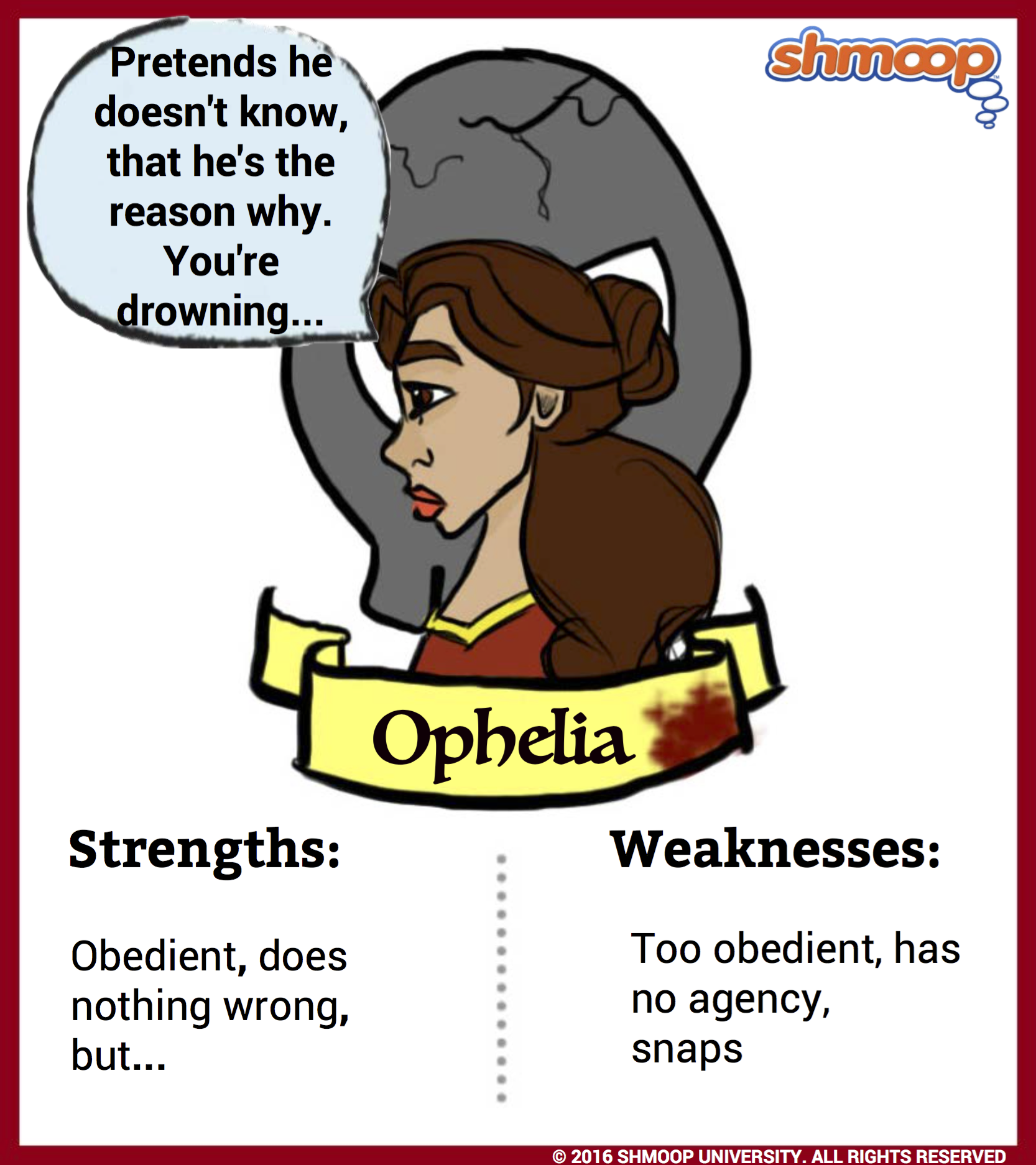

Good Girl Gone Bad

Your parents only wish they had a daughter like Ophelia. When her father orders her to quit seeing Hamlet, she agrees —"I shall obey my Lord" (1.3.145). Later, when Polonius uses her as bait to spy on Hamlet for King Claudius, she does exactly what she's told (3.1). As long as she's unmarried, she lives by her father's rules. (Of course, if she were to marry, she'd then have to live by her husband's rules.) Essentially, Ophelia has no control over her body, her relationships, or her choices.

We'd say she could have used the services of ImperialMatch.com, except that her dad is basically president and CEO of a matchmaking service for one: her marriage is totally in his control.

And eventually, Ophelia snaps—just like a lot of people who spend their lives obeying other people without any sense of personal agency.

Abusive Boyfriend

The problem with being completely obedient and passive is that you can't fight back when you really need to. Hamlet seems to know that Ophelia is helping her dad spy on him, and he accuses her (and all women) of being a "breeder of sinners" and orders Ophelia to a "nunnery" (3.1.131; 132), i.e. a brothel. But she can't call him out on his language, because, as a good girl, she can't admit that she knows what it means.

He keeps going, too. He says that if Ophelia were to marry, she'd turn her husband into a "monster," or a cuckold (cuckolds were thought to have horns like monsters) because she would inevitably cheat on him (3.1.151); and then he follows up these sweet nothings with a little "I loved you not" (3.1.129). Ophelia seems pretty crushed by all this:

And I, of ladies most deject and wretched,

That sucked the honey of his music vows,

Now see that noble and most sovereign reason, […]

out of time and harsh; (3.1.169-171; 172).

But what's her recourse? She can't vent about it on Facebook; she can't even go find herself a nice rebound hookup. In fact, her reputation depends on pretending that she never cared about his at all.

Precious Jewels

Hamlet's not the only one who defines Ophelia by her sexuality. Even her brother has something to say about it. In Act I, Laertes dispenses advice to Ophelia on the pitfalls of pre-marital sex (for women, not men) in a lengthy speech that's geared toward instilling a sense of "fear" into his sister. Just what you want to hear from your brother, right? In fact, he tells Ophelia three times that she should "fear" intimacy with Hamlet.

Is Laertes just looking out for his little sister's best interests? Maybe, but his speech is also full of vivid innuendo, as when he compares intercourse to a "canker" worm invading and injuring a delicate flower before its buds, or "buttons" have had time to open (1.3.43; 44). This graphic allusion to the anatomy of female genitalia turns his sister into an erotic object while still insisting on Ophelia's chastity. Laertes takes a typically Elizabethan stance toward female sexuality —a "deflowered" woman was damaged goods that no man would want to marry.

Which brings us to one important question: did Hamlet and Ophelia actually have sex? We don't know for sure. Shmoop is inclined to think not. What's so tragic about Ophelia (in our humble opinion) is that she hasn't done anything wrong, and she gets destroyed by the patriarchal court culture anyway.

But the possibility's there. Some of the flowers Ophelia gives away during her mad scene (like rue and wormwood) were used for centuries in abortion potions. And there's something pretty suggestive about the fact that she's literally being deflowered—giving flowers away. Would it make a difference if they'd actually had sex?

Ophelia and Madness

Whether they've had sex or not, that's a lot of pressure to put on a young woman. And it's too much for Ophelia. When she goes mad, she sings a bawdy song about a maiden who is tricked into losing her virginity with a false promise of marriage (4.5.63-71)—part of the reason why many literary critics see Ophelia's madness as a result of patriarchal pressure and abuse.

In the end, it kills her. Gertrude describes it to us (seems right that it's another woman):

When down her weedy trophies and herself

Fell in the weeping brook. Her clothes spread wide,

And, mermaid-like awhile they bore her up,

Which time she chanted snatches of old lauds,

As one incapable of her own distress

Or like a creature native and endued

Unto that element. But long it could not be

Till that her garments, heavy with their drink,

Pull'd the poor wretch from her melodious lay

To muddy death. (4.7.199-208)

Notice how her death seems to be passive? Rather than straight-up committing suicide, as Gertrude tells us, she accidentally falls in the water and then simply neglects to save herself from sinking. Ophelia's "garments" "pull" her down, as if they had a mind of their own. This seems to be a metaphor for the way Ophelia lives her life: doing what her father and brother—and boyfriend—tell her to do, rather than making decisions for herself.

Gertrude also suggests that Ophelia's drowning was natural when she describes Ophelia as being like a "native" creature in the water. We also notice that Ophelia is described as being "mermaid-like" with her "clothes spread wide." Even in death, Ophelia is sexy. So, women: natural, sexy … and dead. It seems that there isn't much place for women in the royal court. Will Fortinbras' reign change that?

Ophelia's Timeline